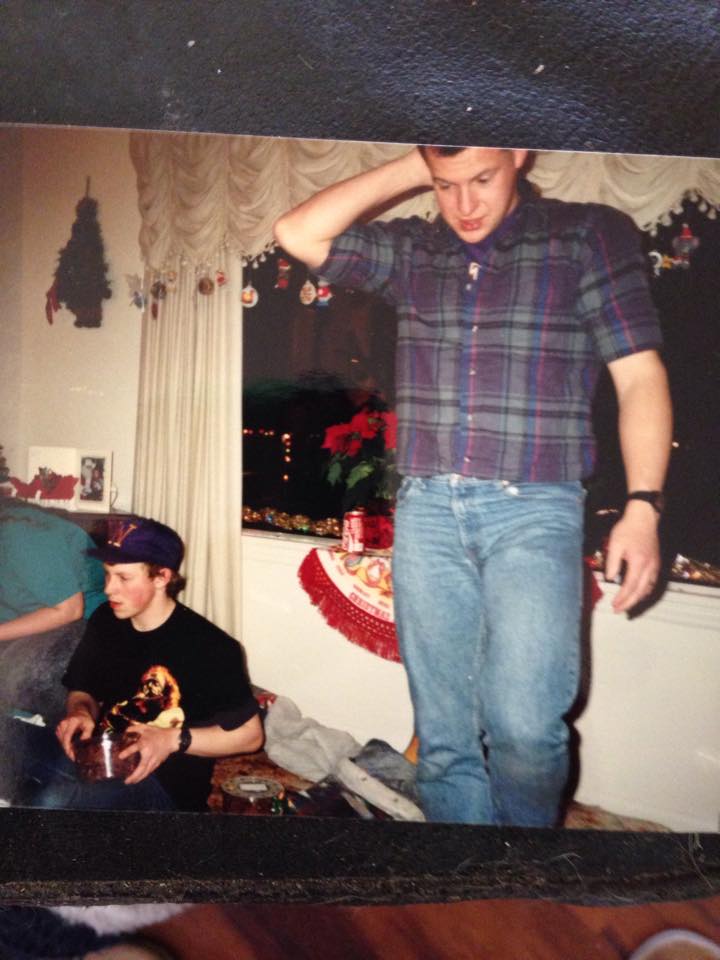

Tomorrow would have been my brother-in-law Bob’s 50th Birthday. Instead, he died three days shy of it while in the hospital awaiting a triple bypass. I think I can safely say I didn’t know Bob well, and yet I knew him as well as most people in his life did. Bob was a quiet man. While he was never officially diagnosed, Jim and I are certain he was on the spectrum. The reason we believe this to be true is because Navy doctors diagnosed Jim with what was then called Asperger’s Syndrome when he was in his 20s. Jim has many neurological differences apparent to those who know him well. Bob’s differences were even more profound and apparent. I suspect to those in Bob’s inner circle, my post-humous, unofficial diagnosis might serve as an ah-ha moment of insight into the man that he was. As I was processing the news of Bob’s death on Thursday afternoon, the first thought that unkindly came to my mind was, “What a shame…to die so young after living such a small life.” And then I really started to think about it. Bob lived with his dad, and before his mom died, he lived with both parents. I’ve heard many jokingly say over the years that he “failed to launch,” and it could certainly seem like that if you didn’t consider or were unaware of Bob’s neurological differences. Except for a brief stint living with Jim and his first wife, Bob never left his parents’ home. He worked the same job for more than three decades – cleaning hot tubs at a nearby hot tub and sauna owned by a family friend. He seldom missed work. He didn’t drive, so he didn’t go out much, but he did love to play laser tag. Jim says he was good at planting in one spot and was the king of the stealth attack because of that. Other players didn’t see Bob coming. I attended many meals and gatherings with Bob over the years. He seldom spoke. He was profoundly shy. In fact, I’d been married to Jim for several years before Bob spoke directly to me. It was Christmas, and Bob came down for the day with his folks to attend our family gathering. I sat down at the piano after dinner and played Christmas carols, and Bob stood nearby with a half-smile on his face. When I switched from Christmas music to Debussy’s Clair de Lune, he closed his eyes for a moment and then opened them, leaned forward, and said to me, “That’s nice.” Holy crap! Bob just talked to me! I was so shocked, my fingers stumbled on the keys. I looked at him sheepishly and shrugged, and he winked. Or at least I think he did. Bob and I had shared a moment. That was the year Bob won the lottery--$100K on a scratcher. With the money, he paid off his mom’s medical debt, gave his nieces and nephews each $200 gift cards for Christmas, bought himself a motorcycle, and took a trip to the Super Bowl. I never really had a full conversation with Bob, and yet I knew him in the way that most people were able to. Over the years, he said small things here and there, but mostly he sat quietly and observed, seldom speaking. When he joined Facebook years ago, he started commenting on my various posts. And knowing Bob, I understand this: it was his way of having a relationship with me, and it was the best way he was able to do so. I always appreciated that he reached out to me in that way. Jim and I were talking Thursday night as he processed the news of Bob’s death. “I feel like I should learn something from this,” he told me. “What do you mean?” I asked. “I’m not sure…something about living instead of being afraid to live.” And I understand. I do. Because my first thought was about the apparent sadness of dying at 49 after a small life. And I thought of the many people who live apparently small lives, quiet lives, lives of solitude. Lives of neurological difference. For me to dismiss their lives as small or lacking in impact is both unkind and untrue. And I don’t think Bob was afraid to live. I suspect he had extreme social anxiety, and I think he lived as he needed to feel comfortable and safe. So, I thought a little more. I thought about Bob and the things I knew about him, and I know his life, no matter how small it might appear to others, mattered. Bob’s life wasn’t small. It was, however, contained. He kept his circle small and his communications quiet. But these are the things I know to be true about my brother-in-law. He was loving and loved. Bob lived with his mom and dad his entire life. And they loved him. His continued presence brought joy to his mom, a joy she was able to experience until the end of her life. And he loved her back. He loved her so much he dedicated his life to being with her and taking care of her. And, when his mom died, Bob provided companionship to his dad, who would have felt deeply alone in the wake of his wife’s death. He was important to both his parents, and he provided support, love, joy, companionship, and comfort to them for his entire life. Bob was loyal. He worked at the same job for more than 30 years. He was loyal to his brothers, his nieces and nephews, his parents, his aunts and uncles, and all the various spouses. While he didn’t say much, he was present. When we gathered, he came. He was responsible. Bob seldom missed work; when he did, it was for a good reason. In fact, after his heart attack last week, he went to work and insisted on staying the entire day. He also used his income to help his parents with the bills. He paid the few bills he had. He wasn’t frivolous. Bob was generous. When he won the lottery, he paid off his mom’s medical bills. He gifted his nieces and nephews. He didn’t selfishly hoard his winnings or spend them on just himself. A man who didn’t have much by way of his own wealth shared his good fortune with the people he loved. I also observed him donating his limited funds to fundraisers on social media, so although he didn’t have much, he was not just content with what he had, but he shared it with others as well. He was a dreamer. A guy who never got a driver’s license and was, in fact (at least according to his older brother) impossible to teach to drive bought himself a motorcycle when he won the lottery. I see that as an optimistic and hopeful act – a bold statement of a dream he held for himself that he set about trying to make a reality. Bob cultivated joy. Maybe others wouldn't find the things Bob liked to do interesting, but nevertheless, Bob did things that made him happy. He played laser tag and was, by all accounts, extremely good at it…good to the point that he laser tagged in championships. He went to the Super Bowl because he loved football. When opportunities arose, Bob chose things that made him happy, and he didn’t hold back. He participated in those activities with 100% of his being. He was unapologetically himself. Many people with neurological differences and social anxiety feel pressured to behave in ways that make them profoundly uncomfortable but make the rest of the world comfortable. Bob saw no reason to do that. Instead, he was always 100% exactly who he was, and he brought that into every aspect of his life. Bob lived a contained life, but it wasn’t small, and it wasn’t wasted. Instead, he lived his life his way, making the most of who he was and the values he held. And while his circle was small, he made an impact. People loved him, and he loved them back. He was quiet. He was contained. He was an observer. But he made a difference, and it’s sad that so few people got to know him. He lived his life, his way. And in doing so, he had an impact on those he chose to know and those who chose to know him.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Categories

All

Archives

December 2022

|

AUTHOR KAREN FRAZIER

- Home

-

Books

- Angel Numbers for Beginners

- Avalanche of Spirits

- Chakra Crystals

- Complete Reiki

- Crystal Alchemist

- Crystals for Beginners

- Crystals for Healing

- Dancing with the Afterlife

- Dream Interpretation Handbook

- Essential Crystal Meditation

- Higher Vibes Toolbox

- Introduction to Crystal Grids

- Little Book of Energy Healing Techniques

- Noisy Ghosts

- Reiki Healing for Beginners

- Transform Your Life with Alchemy

- Ultimate Guide to Psychic Ability

- Usui Ryoho Reiki Manual

- Cookbooks

- Other Books

- Classes

- Connect

- Meditate

RSS Feed

RSS Feed